People open museums for lots of reasons. They want to educate, they want to bring their community together, they want to display their fantastic collection of This And That— but overwhelmingly the reasons boil down to love. They love American Colonial history or photography or mediterranean art so much that they had to dedicate an entire space to it that anyone can go to at any time and be surrounded by the love that someone has for this thing.

At the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum on Staten Island, the love for Italy and their Italian heritage is abundantly apparent.

The Garibaldi-Meucci Museum was the home of inventor Antonio Meucci and was a boarding-house that General Giuseppe Garibaldi stayed in for several months after the first Italian War of Independence. The house was moved to its current location and dedicated as a memorial site to Garibaldi in 1907, and in 1956 was opened as the Garibaldi-Meucci museum, dedicated to the lives of the two men and to the Italian and Italian-American population of Staten Isalnd.

I was greeted at the door by an affable tour guide with an ice-cold bottle of water for me. It was a charming little cottage to walk into out of the summer heat, and nearly made me forget how terrible the public transportation on Staten Island is.

I was led into a room dedicated to Giuseppe Garibaldi, and my guide started in with the story.

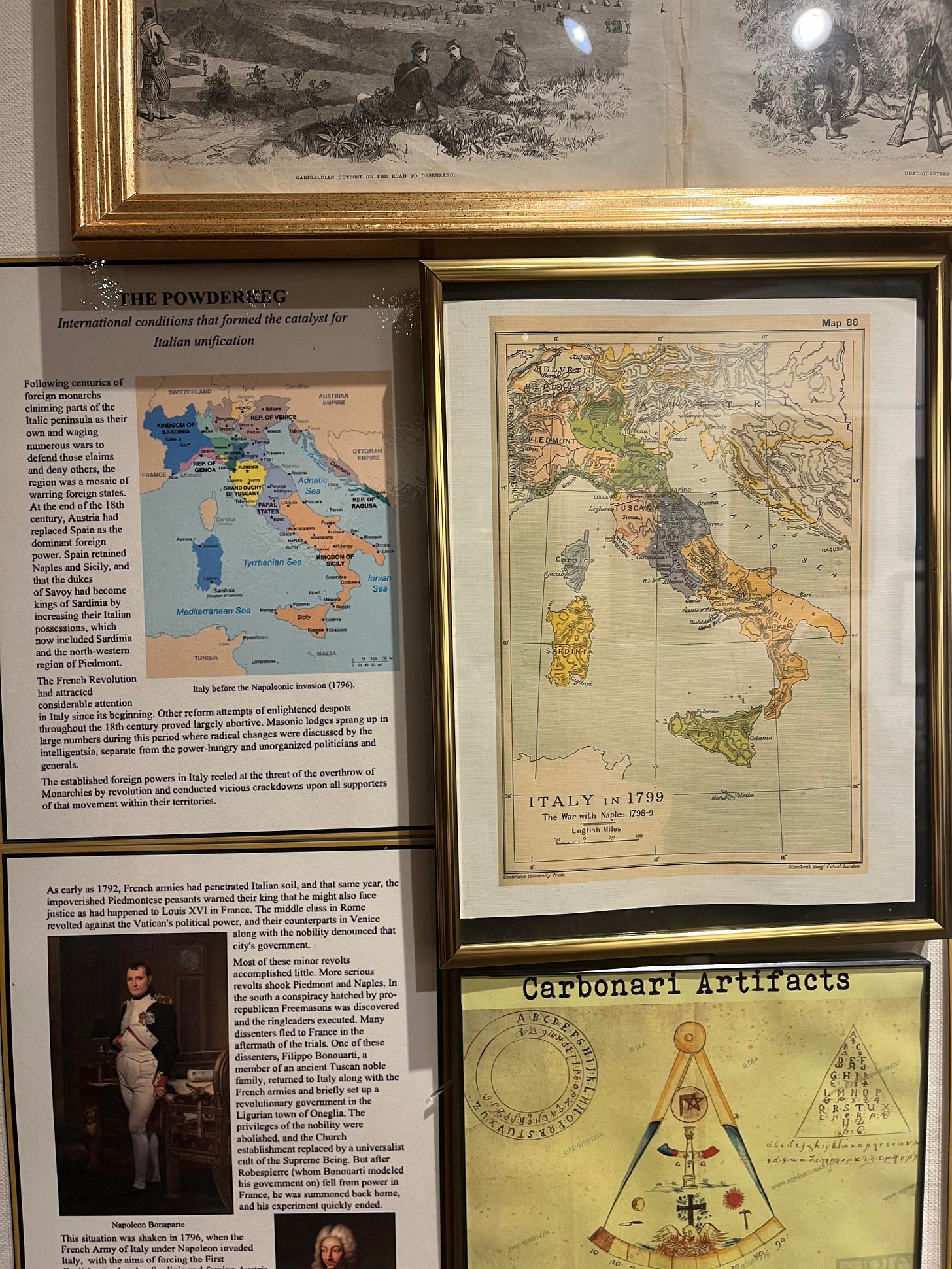

In 1807, when Garibaldi was born, Italy as we know it did not exist. It was instead a loose collection of states which included the Kingdoms of Italy(the upper right half of the boot), Naples(the lower half of the boot), Sicily and Sardinia. The upper left half of the boot was controlled by the French Empire. The 19th century played out a number of revolutions which eventually united what we now know as Italy into a single composite state— and Garibaldi played a major part in it.

Under Garibaldi’s leadership, the Sardinian monarchy united with the Kingdom of Italy politically, and Garibaldi and his volunteer army(the Redshirts) personally oversaw victories overthrowing the French and Austrian governments at Varese, Como, Nice, Sicily, and eventually, with the help of the Royal Sardinian Army, Naples, which was the deciding victory of the war.

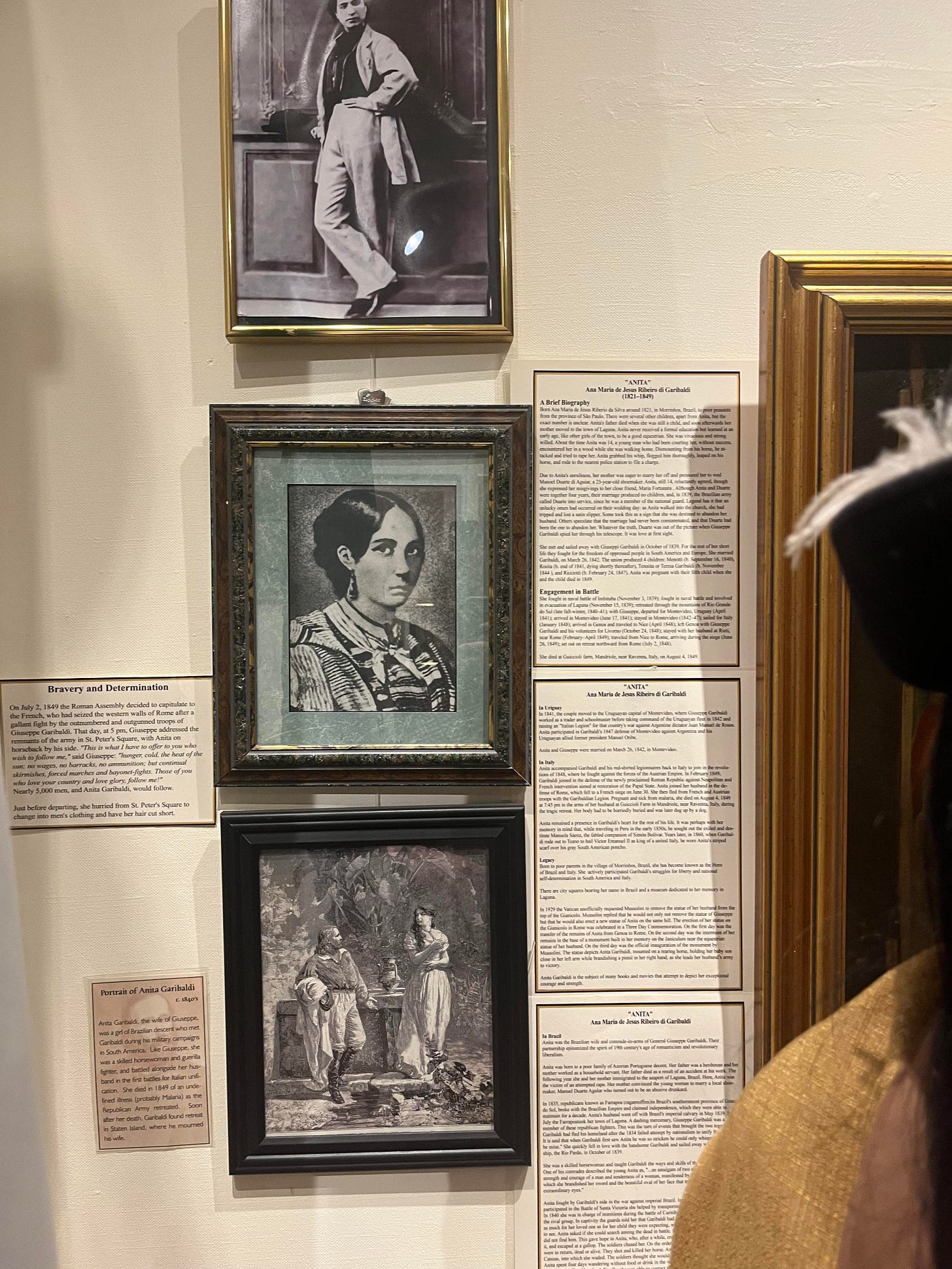

A portion of the room was dedicated to his wife, Ana Maria de Jésus Riberio di Garibaldi. She was a peasant woman from Brazil that Garibaldi met when he was stationed there to aid in a revolution on behalf of the Piratini Republic who had seceded from Brazil in order to create a constitution freeing their slaves. Though they eventually became part of Brazil again, the Brazilian constitution from then on(1845) contained articles of slave abolition.

Ana was a fighter in the revolution in her own right— in one account she led troops into oncoming battle, shielding them in her knowledge that the other side would not shoot at a woman. She remained by Garibaldi’s side through his many victories until she died from malaria while fleeing from French and Austrian troops just before Garibaldi went to America.

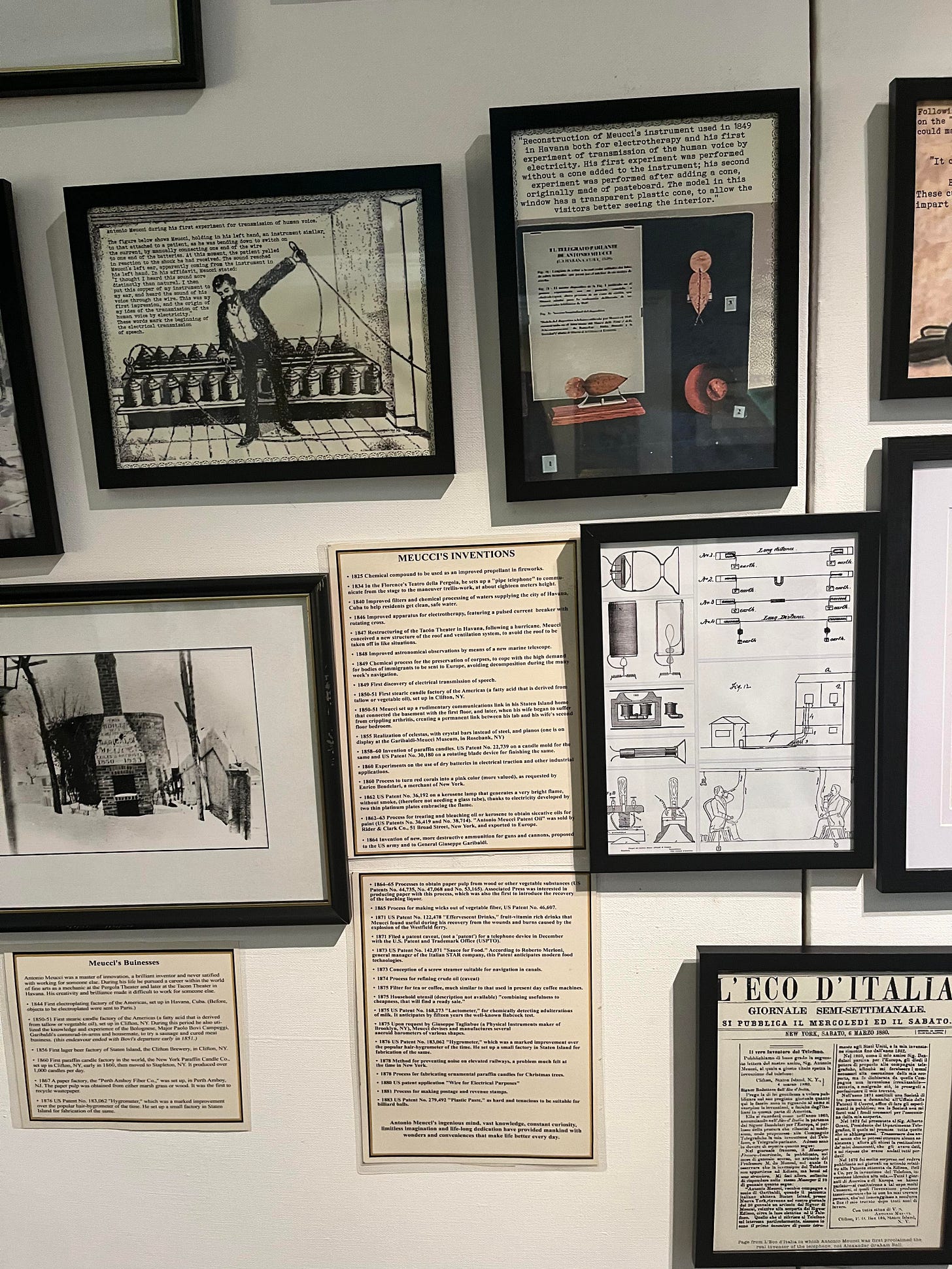

The next room was dedicated to the inventor Antonio Meucci. Meucci was born in Italy but lived in America for approximately the last forty years of his life. His most significant invention was a voice-communication apparatus that many people(including, without a doubt, my guide) credit as the first telephone, at least five years before Alexander Graham Bell submitted his patent for the telephone we know today.

One of the first and major ways that Meucci’s talents for engineering and invention was in the opera house he worked in. As many readers of this blog know, I work in technical/backstage theatre in New York, and was delighted to find this connection. His wife, Esterre, was a costume designer and seamstress and Meucci came up with several ingenious inventions for the stage, including a system of pipes running through the space so that someone speaking from the front of house could be heard by someone in the orchestra pit, and a system to make all of the foot lights at the front of the stage extinguish at once— perhaps one of the very first lighting cues!

The story of Meucci’s work with the telephone is that he had been experimenting with electromagnetics as a cure for migraines, but found that when one of his patients was speaking near a charged electromagnet(i.e. one he attached to their tongue), he could hear them clearly from several rooms away. After much tinkering, he installed several communication lines in his house, so he and his wife could communicate from wherever they were. He submitted a patent caveat for this device in 1871, but it expired the next year and five years later Alexander Graham Bell was able to successfully file for a full patent.

Upstairs was a recreation of the sparse room where Garibaldi stayed when he was living with Meucci in Staten Island. It was a cozy space, if a little small for a significant Italian general.

Back on the first floor there was a room that housed a rotating gallery of Italian and Italian-American visual artists that the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum wishes to showcase. When I visited, it was a collection by Emilio Giuseppe Dossena, who was born in Italy in 1903 and moved to New York in 1968. Dossena was a skilled painter in both the schools of impressionism and expressionism who showed his work in spaces as prestigious as the Galleria Hoepli in Milan and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Garibaldi-Meucci museum is a space that is welcoming, warm, and above all incredibly informative. If you had asked me at this time last week when Italy was unified I would have said something along the lines of “Um, the Roman Empire?”, but I walked away from this museum with an entire story of a country that came together and the man that led them. It remains, in my opinion, unclear who truly first invented the telephone both in a practical and a legal sense, but I now know some of the stories of the man who may have made the first theatre lighting cue, and I feel closer to the work that I do and to him because of it.

ADMISSION: $10

GIFT SHOP: Yes

BATHROOM: Yes

WHEELCHAIR ACCESSIBLE: No

June 29: General Grant National Memorial

July 6: Break!

July 14: Godwin-Ternbach Museum

July 20: Governors Island National Monument

Among other things I am impressed that this writer clearly does research and gives us facts, because honestly that’s not wholly necessary — my favorite parts are when she gripes about the MTA (so many trips to Staten Island!) or describes the invariably nutty tour guides. But anyway. This substack is brilliant