The Drawing Center was not my first choice of a museum to visit this past weekend.

Make no mistake, I have been greatly looking forwards to visiting this museum for some time. To give you a look behind the curtain, though, I must let you know that I am not finished with the museums beginning with "C", or, indeed even with "B". I am deeply in alphabetical-order museum debt with museums that have decided to make it very difficult to visit. This weekend I first tried to go to the Cooper Union Galleries but found that they currently have nothing on display, then was almost on my way to the Derfner Judaica Museum before I realized that it required me riding the 1 train to the end of the line into the Bronx and then walking 45 minutes in the rain.

So I showed up at the Drawing Center, pleasantly surprised to be showing up several weeks ahead of schedule.

The drawing center was founded in 1977 by Martha Beck, a former curator at the Museum of Modern Art. It is the first and only museum in the city of New York dedicated specificially and exclusively to the art of drawing. It was initially housed in a warehouse space in SoHo but in the late 1980s moved to its current home of a pre-war cast-iron-fronted building in Tribeca.

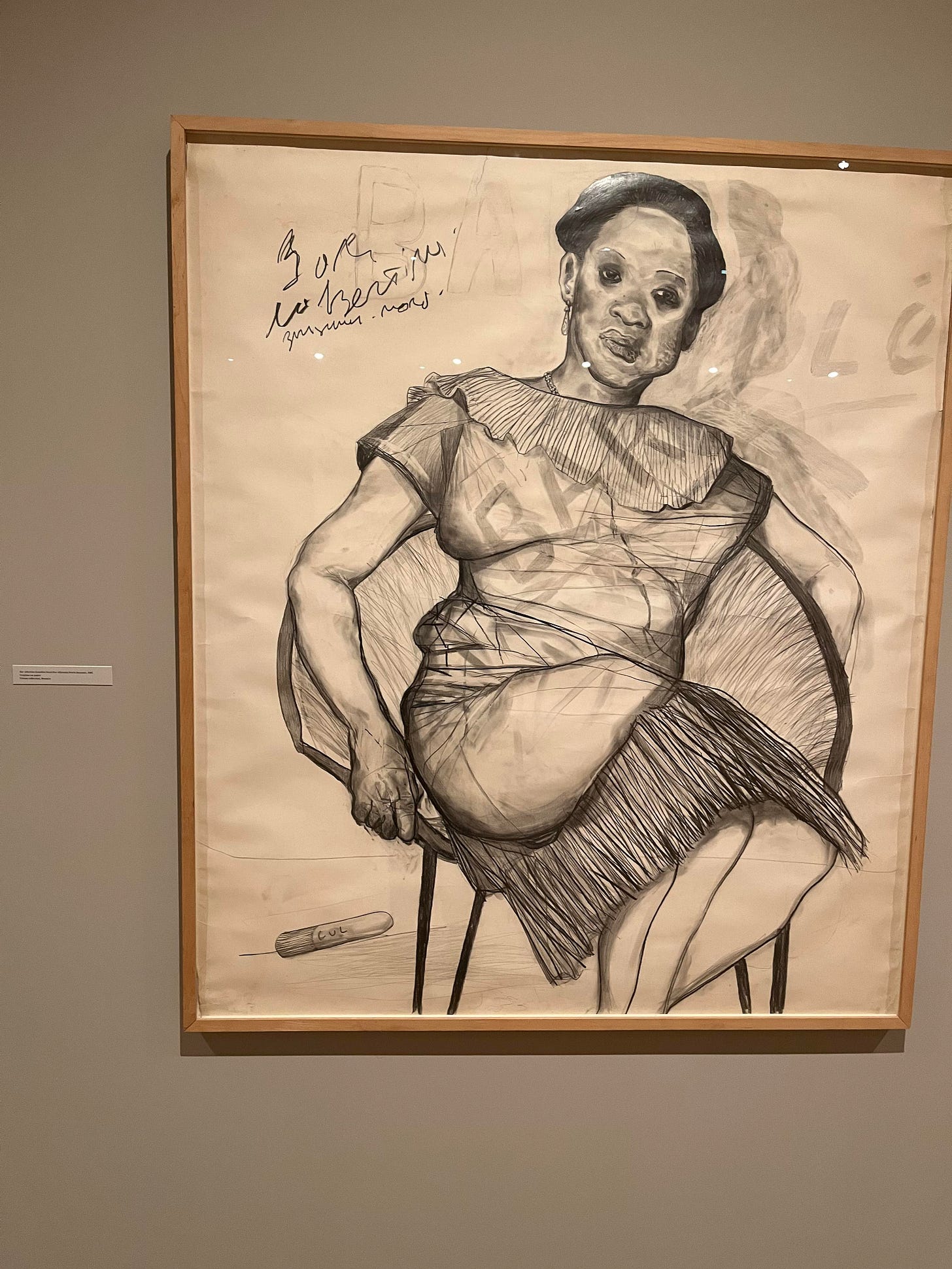

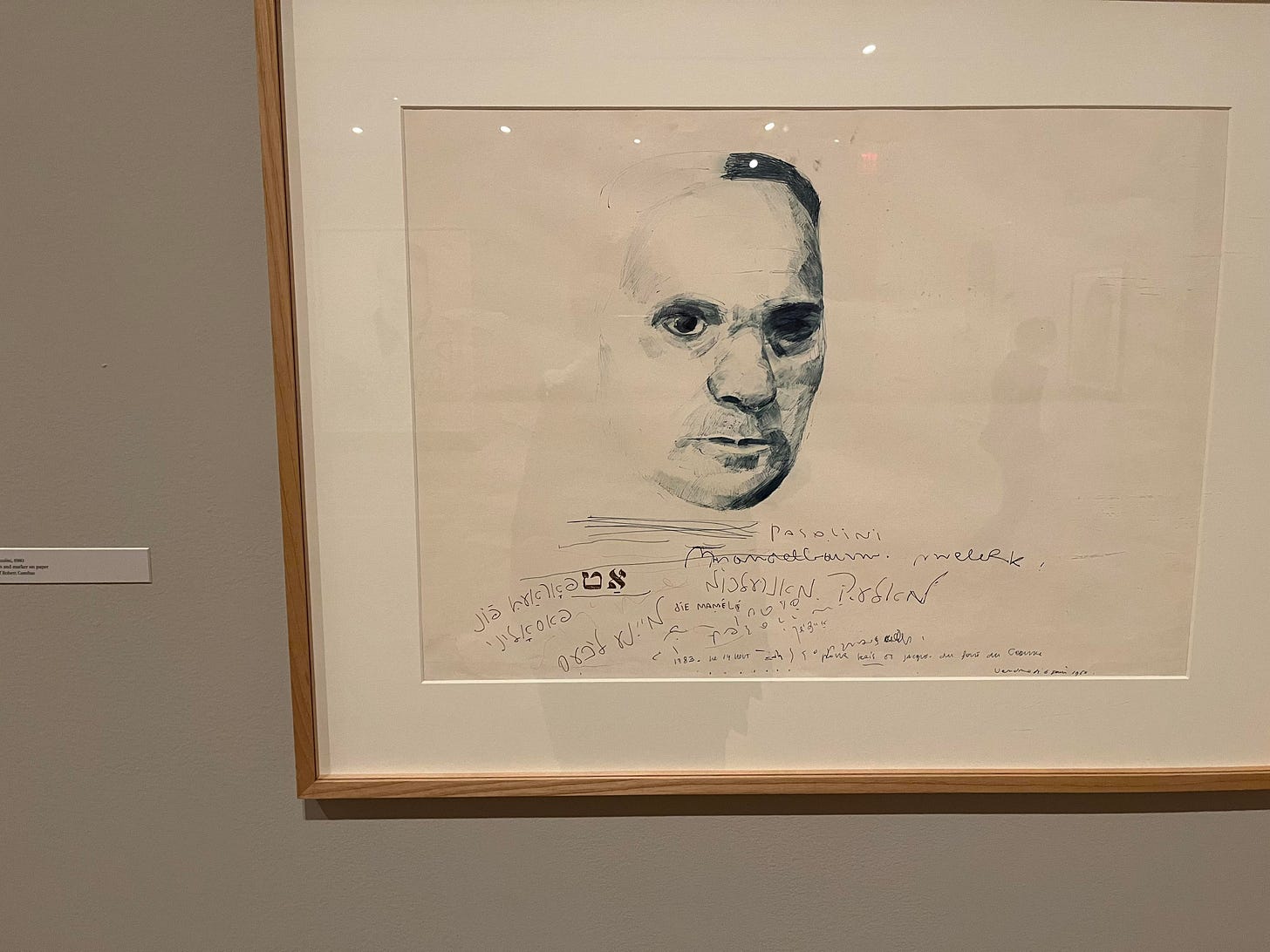

They had one exhibtion hall open at the time that I visited, and it was dedicated to the works of Stéphane Mandelbaum. Mandelbaum lived in Brussels in the 1960s and 70s and was a child of Holocaust survivors. His works explore his relationship with his friends, family and lovers and the impact that Nazi Germany had upon his life and upbringing. His torrid life in Brussels would meet a violent and sudden end when he was killed by a criminal syndicate after a bad art forgery deal fell through in 1986 at age 25.

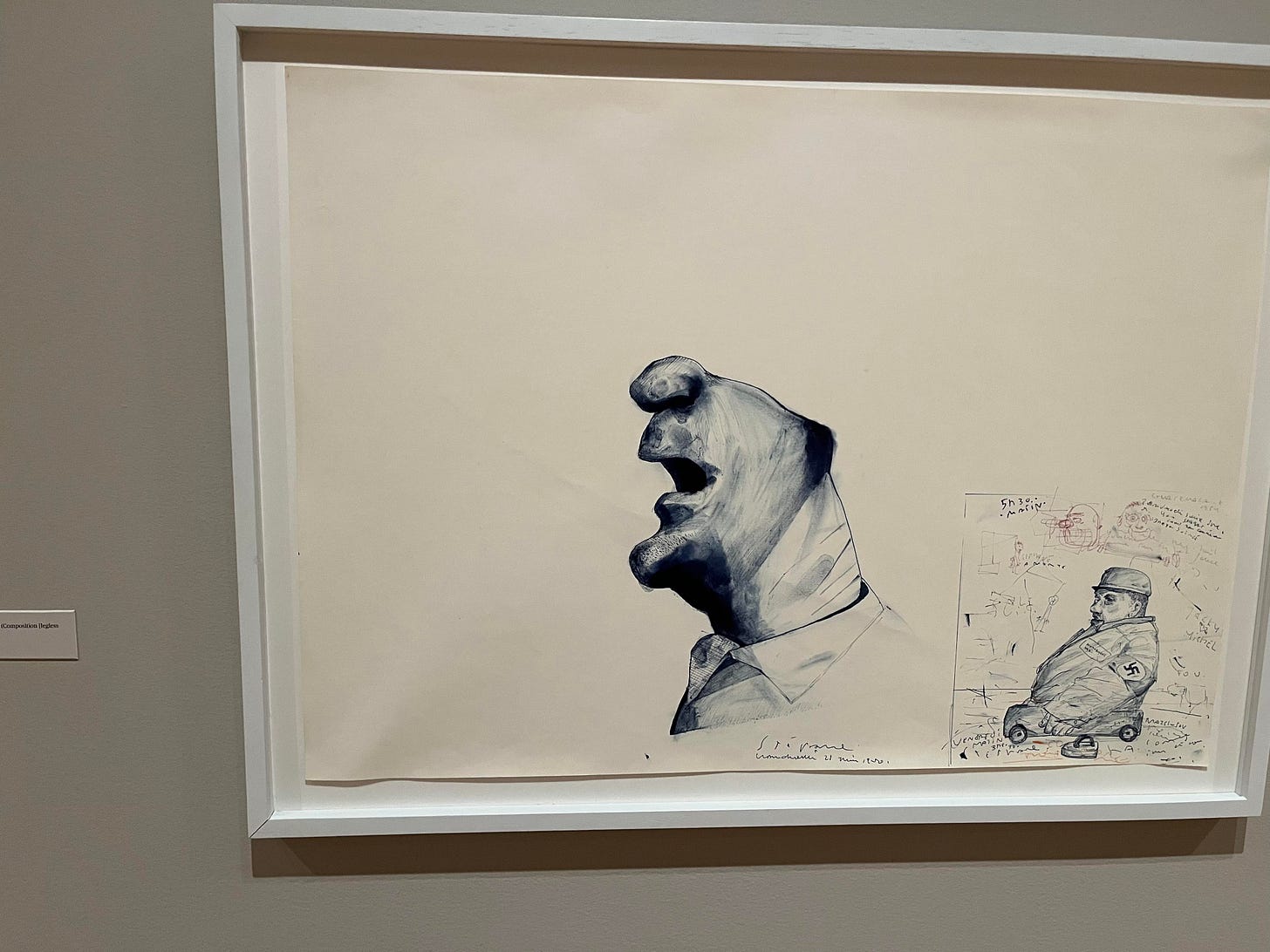

A noteworthy throughline from Mandelbaum’s work is his tendency to visibly let his mind wander— to include doodles and notes in various languges in the margins and sometimes the center of his drawings. These remnants and sketches of thoughts are soemtimes clearly related to the subject matter at hand but are sometimes only tangentially so, letting the viewer try to puzzle out why he wrote about an oyster soup on a portrait of a filmmaker friend of his.

Sometimes you have to work your way around a project in interesting ways. Sometimes you fill the corners of your nazi portraits with drawings of Tintin characters, and sometimes you skip several museums ahead for a week. Whether we can clearly see them or not it is these deviations from the plot that makes any piece of art interesting to behold and it is always good to be reminded of that.

I love these drawings! Especially love the man with just a head connected to pants (7th pic).

You are so great at this!!!!